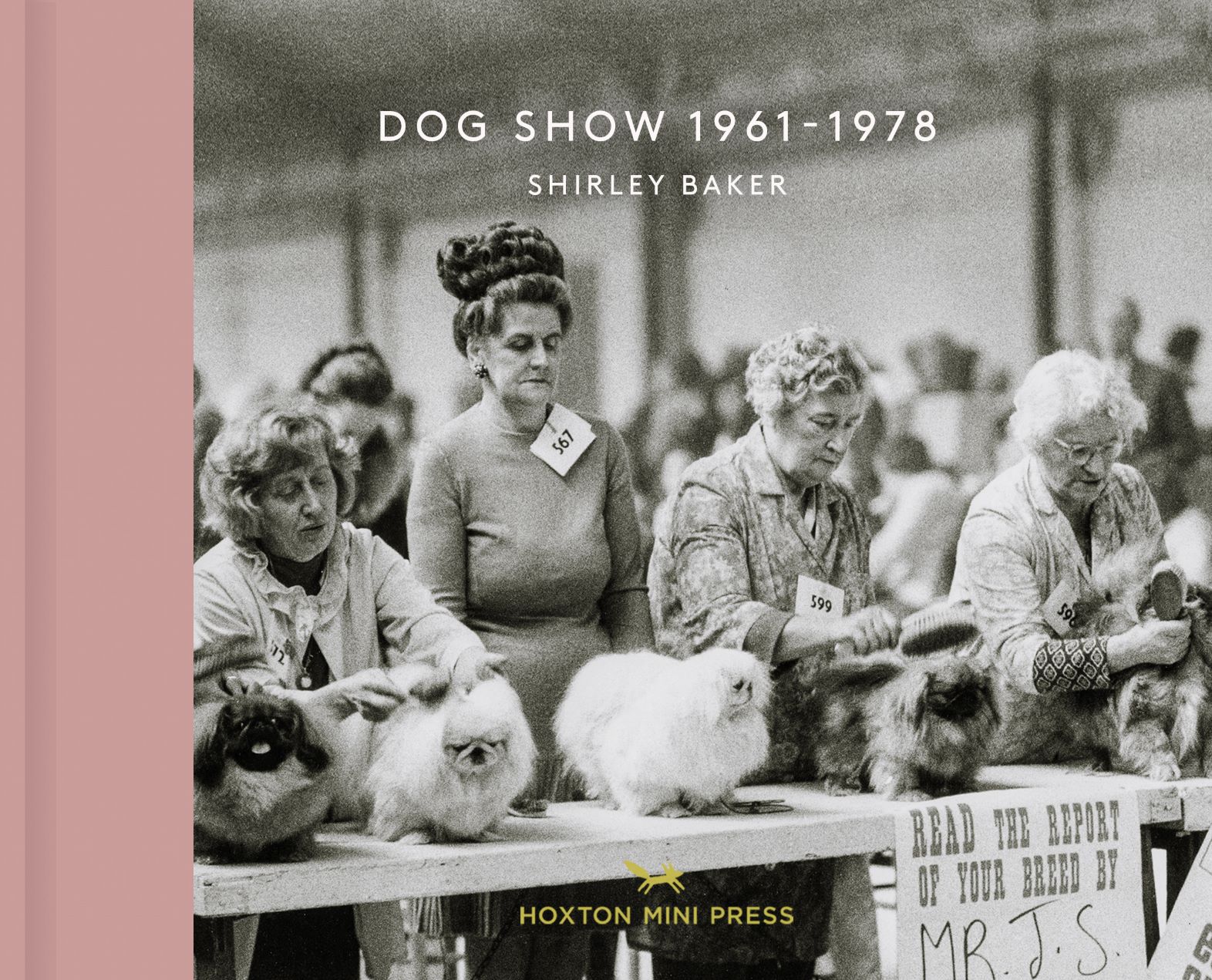

To honour the publication of Dog Show, showcasing the work of photographer Shirley Baker, which is featured in November’s The Simple Things, we’ve made a list of our top five fictional dogs. Now, SIT! (And read and enjoy our best in show).

Snoopy (beagle*)

A real case of the side-act stealing the show, Snoopy was the pet of Charlie Brown, anti-hero of the Peanuts comic strip. But there’s no denying he was the real star. Known for sleeping on the uncomfy-looking roof of his kennel rather than the inside, having several alter-egos including college student, Joe Cool and a First World War Flying Ace, as well as his unlikely friendship with a yellow bird, Snoopy is world-famous and has appealed to generations of children (and beagle-loving adults). An icon in his own right, the first drawings of Snoopy were based on Charles M Schulz’s dog, Spike. *He’s always referred to as ‘a beagle’ but Schulz once said he wasn’t, he just thought ‘beagle’ was a funny-sounding word.

Snowy (wire fox terrier)

Tintin’s faithful friend Snowy is the only other character to appear in all the comic albums, he even occasionally addresses his internal monologue to the reader. Very postmodern. His original name in the French was Milou, the name of Herge’s first girlfriend, and short for Marie-Louise. He was called Snowy in the English translation for his white colour (and the fact that Snowy was short enough to fit easily into the speech balloons.

Lassie (rough collie)

Lassie first featured in a short story by Eric Knight, which later (in 1940) became a full novel, Lassie Come Home, and was made into a film by MGM in 1943, with a dog named ‘Pal’ acting in the title role. The story may well have been based on a fictional dog called Lassie depicted by Elizabeth Gaskell. Pal’s descendants continued to play Lassie in TV series over the next 20-odd years, scampering off to rescue many a child from a mine shaft or well. GOOD GIRL, Lassie.

Scooby-Doo (great dane)

Comrade and crime-busting partner of Shaggy Rogers, Scooby-Doo is the true hero of the Hanna-Barbera series that began in 1969. Famously named for a line in the Frank Sinatra song, Strangers in the Night, Scoobs has been foxing fairground thieves and eating multi-layered club sandwiches for years and continues to delight children to this day.

Argos from The Odyssey (breed unknown)

Hankies at the ready. Argos was Odysseus’s dog before he left home to fight in the Trojan war for ten years, and then spent a further decade returning home. When he finally returns, disguised as a beggar to fool his wife’s suitors, he sees Argos, his faithful, strong and speedy hound, sitting in pile of cow muck. As he walks by, Argos drops his ears and wags his tail but is physically unable to greet his master. Odysseus cries as he passes him, unable to go to his faithful friend. And Argos dies, having fulfilled his destiny of welcoming his master home to his own hall.

Jumble from The William stories (mongrel)

Jumble originally belonged to an artist and his daughter and the daughter gave Jumble to William in exchange for a kiss. Knowing William’s liquorice-water-encrusted chops as we do, we think William got the better end of the deal there and Jumble went on to be (almost) the fifth member of The Outlaws.

Toto from The Wizard of Oz (some sort of Terrier)

Toto belongs to Dorothy Gale of ‘there’s no place like home’ fame. He’s been variously thought to be either a Cairn, Yorkshire or Boston Terrier and he accompanies Dorothy on her trips to the Land of Oz. Toto does not let on in the early books - not until TikTok of Oz - that he can speak! Really, you might have mentioned this before. Toto!

Gnasher from The Beano (Abyssinian Wire-haired Tripe Hound)

Dennis the Menace’s faithful and (very) furry friend Gnasher first appeared in The Beano in 1968. He was based on the idea that dogs look like their owners and it was suggested to the illustrator that he simply drew Dennis’s hair and added arms, legs and eyes. And that is (more or less) how Gnasher remains to this day, with just a little more of his own character.

Gromit from Wallace and Gromit (Beagle)

The bright, sensitive, brainier half of Wallace and Gromit, this is a mutt with a hardcore fanbase. His birthday is 12th February (and it is marked every year in The Telegraph’s classified section), he’s known to be left-handed (a sign of his creativity and intelligence) and a NASA robot sent to probe Mars was named after him in 2005. He also loves cheese (who doesn’t?).

Pilot from Jane Eyre (Newfoundland)

Mistaken on first meeting, by Jane, as some sort of ghost-dog or dog-goblin (a doblin, perhaps?) Pilot foreshadows Mr Rochester’s entrances throughout the novel and is the first to call Jane to Mr Rochester’s aid as his horse slips on icy ground. Rewarded with so little as a cursory ‘DOWN, PILOT’ the dog is peeved as always, while Victorian women swooned, as one.

Our fictional dogs were inspired by a gallery in our November issue, taken from the book Dog Show: 1961-1978 by Shirley Baker, published this month by Hoxton Mini Press.

Get hold of your copy of this month's The Simple Things - buy, download or subscribe

More from November issue…